A client recently asked me to assist them with a win-loss analysis of a loss for which they were nearly 10 times (!) the winner’s price. While the source selection used by the customer was “lowest price technically acceptable (LPTA),” which can lead to some odd pricing behaviors, my client was convinced the competitor was behaving irrationally, and that their pricing was unsustainable in the market. I countered that the competitor was behaving rationally and that their behavior was part of an intentional business strategy. Before I reveal why I believe I was right, it’s important to understand why the line between extreme rational and irrational pricing can become blurry.

Know your Competition

Understanding your competition and their ability and appetite for pricing aggressively, as well as their desire to further their strategic objectives, is paramount. Spending a few hours digging through corporate filings, recent press, company websites, and prior bids via Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests or sources like BGov and Deltek GovWin can be invaluable in determining whether competition is going to push the extreme rational pricing envelope and really lean into an opportunity. What do I look for in this process to indicate that a competitor may be aggressive with its pricing? For starters:

- Recent press announcements, investor briefings, and/or critical hires indicating expansion into a specific industry, solution, and/or customer segment

- Recent win on a multiple-award contract with the initial task orders now being competed

- Multiple consecutive task order losses on a critical multiple-award contract

- Winning a large department-level contract—like DHS, DOJ, or the US Army—with the sub-agencies/bureaus now issuing procurements for nearly identical products and/or services

- Explicit competitor statements that they are targeting an incumbent’s contract.

It is also important to understand your competitor’s financial position and inclination to take on risk to determine their willingness to push the boundaries of rational pricing. Many companies take a “portfolio view” of their current and potential opportunities; therefore each individual opportunity can be viewed as financially accretive or dilutive (for both revenue and profit). A competitor that is in a strong financial position might be willing to forgo some revenue and/or profit in the first couple of years of a contract to increase their pWin (probability to win). They can give the program manager the responsibility to make up any financial shortfalls over the entire contract period. I’ve worked with many organizations that have required such a “get well plan” at bid submission so that everyone is comfortable that short-term financial sacrifices will be made whole in the future.

Competitors have also been known to price very aggressively when seeking expansion into a new market. It is significantly cheaper for a company to price an opportunity at (or even below) break-even to secure a win and kickstart a new market than it is to acquire the company that wins.

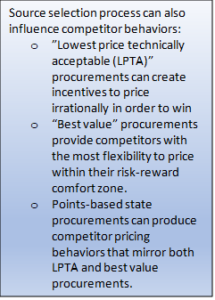

Know your Source Selection Process

In the federal environment, the source selection typically falls into one of two buckets—“lowest price technically acceptable (LPTA)” or “best-value trade-off.” LPTA procurements clearly offer the best opportunity to push the rational pricing boundaries just by the nature of the evaluation process. The “technically acceptable” part of the evaluation process is highly subjective and a low threshold to meet. Therefore, a bidder must truly understand how critical the opportunity is for their strategic objectives, how much potential financial and execution risk they are willing to take on to win the opportunity, and the absolute lowest price they can offer that meets their risk profile. In my opinion, if a company states that the proposed price meets those three criteria, then that is the lowest rational price they can propose, and anything else crosses over into irrational behavior.

As for best-value procurements, companies can offer discounts and other incentives to drive down their price and potentially increase pWin. An offeror with the highest score on the non-price factors and the lowest price will win the procurement, and a company that offers superior value need not always offer the lowest price. However, understanding the procuring organization and their willingness to leverage a best-value trade-off process is important. Often, non-price factors differ little, so price becomes the determining factor. Therefore, a company willing to push the bounds of rational pricing can overcome a company with a superior solution simply because the price differential is too great to pass up. Case in point: I had the pleasure of attending a debrief at which the procurement official said they selected the winner because the price was so low, they could effectively fail halfway through, start over, and do it right the second time before they spent the amount of money that anyone else bid.

In state procurements, the source selection is often point-based. In these procurements, the lowest price offeror typically receives all the price points and the remaining offerors are allocated points based on a mathematical formula. The intent of the point system is to reflect a “best-value” evaluation model. The reality is that, in most cases, there is a price point that is sufficiently low to not only enable a competitor to receive all the price points, but also create a sufficient gap in the price scoring that cannot be overcome in the non-price point allocation, thus creating a de facto LPTA evaluation model.

Understand the Evaluation Model and its Ability for Gaming

The last area for pushing the rational pricing boundary is the price evaluation model itself. These models are often explicitly labeled “for evaluation purposes only,” which provides offerors the opportunity to make extreme assumptions under the premise that the model’s elements may be subject to contract modifications/negotiations in contract execution. If the model is heavily weighted towards expiring technologies or resources that are unlikely to be used, an offeror can provide pricing that may pass a statutory fair and/or reasonableness test, but does not meet a “reality test” and provides an artificially low evaluation price.

… And the winner is—Extreme Rational Pricing

So back to my client and their recent loss. Applying what we just learned about understanding the competition, the source selection process, and gaming the evaluation model, it appears the winner pushed the boundaries of extreme rational pricing:

First, the competitor had sold a segment of its business in the year preceding the procurement and sought a return to that customer segment. This opportunity was perfect for them and they were willing to risk a couple years’ minimal or no profit as the cost of buying back into the market.

Second, the LPTA evaluation model created the perfect opportunity to price at or below the very bottom of the market.

Third, the evaluation model itself provided the final gaming opportunity. The model was weighted heavily towards an expiring technology that would be phased out within the first two to three years (of a 10-year contract). Thus, the competitor would have the opportunity to migrate the customer to a more expensive (and likely more profitable) price point over time because the product lifecycle would require a change. The competitor simply took advantage of this knowledge to drop the unit price of the expiring (and overweighted) technology to a price point that exceeded everyone else’s risk profile. So, what seemed to my client like unsustainable pricing from an irrational competitor turned out to be a savvy move by an informed negotiator.

Learn more about Hinz Consulting here.

Join the Conversation